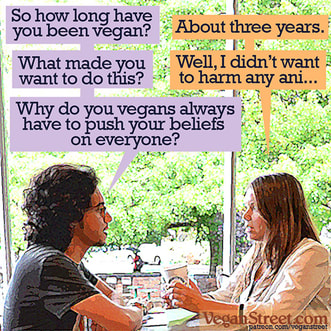

This is a statement that I have heard a few times recently.

As veganism has become more popular, it has triggered pushback. When I began doing vegan activism in the 1990s, vegans weren’t seen as a threat to animal agriculture or to people’s coveted family or religious traditions. Grocery stores, hospitals, and local TV news welcomed me and repeatedly provided venues for me to criticize animal exploitation while encouraging people to give veganism a try. Some were inspired or motivated to change as a result of this. Those who didn’t “get” my message or disagreed, ignored me and moved on. Since vegans were so rare, this message was a curiosity not a threat.

But now, almost everyone in America knows there are millions of vegans. Veganism is a viable lifestyle AND growing in popularity! Vegans are setting athletic records, running successful companies, and birthing and raising healthy vegan families. This changes everything. Conscious of it or not, those who are not yet vegan live with the continuous discomfort that they are participating in unnecessary violence against other beings. Unlike the 1990’s, now simply saying, “I am vegan” reminds non-vegans they are not living consistent with two of their own values which are also widely held. Most of us agree: It is wrong to unnecessarily harm animals. Most of us also agree: It is wrong to unnecessarily hurt your neighbors or your children and grandchildren. (Animal agriculture is a leading driver of every category of environmental destruction -- most especially climate change!) Just BEING vegan around some people feels to them, like they are being attacked because it's reminding them of their complicity.

But those who DO embrace veganism, struggle with a different discord – feeling like an outcast from their tribe, family, or social group. Any choice that sets us apart from our group, can expose us to “change back.” Pressure.

In order to help you understand why, saying, "I am not that kind of vegan" is problematic, I will share with you what happened to me as a child.

The children in my neighborhood wore the trendiest clothes and enjoyed the latest, greatest toys and gadgets provided in mind-numbing abundance at least twice each year. Their pantries were stocked with an array of seductive junk food.

But that was not how it was at my house.

Grade school was hell for me. I was taunted for being fat and for not dressing fashionably. “Highwaters!” my classmates shrieked as they pointed at my too-short jeans before running away. Everyone knew I was part of a small group of outcasts. We were the “untouchables” of our grade. Included with me was the other heavy girl, a thin shy girl with terrible acne, a white haired, poorly coordinated boy, and a scary boy who hit and never followed directions. Just above us in the hierarchy were a handful of students who although not as openly shunned were still avoided. The hierarchy was made visible and reinforced through the act of picking teammates or partners for activities.

You might think those lower down in this hierarchy, experiencing this injustice would be the first to challenge it or at least not do the very same thing to others. But in fact the opposite happened. The more oppressed one of us felt, the more intensely we distanced ourselves from anyone with low status. We feared more oppression if associated with any of the other victims.

My observations are consistent with what’s been documented in other cases of oppressed groups. Time and again, those concerned with their own inclusion contribute to the victimization of others --be it the class system of India, oppressed US minorities trying to better their own lot (and being called, “uppity” by others likewise oppressed) and some women struggling for position in male dominated arenas.

One common way this pressure can be managed is to distance ourselves from those the dominant group find most problematic. Supporting the oppressor’s perspective – even just in a tiny way, can ease some of the pressure, by aligning us – at least in part with those who hold the power. In other words, some vegans join the oppressive class and throw vegan activists under the bus, to help insulate themselves from the “change back” pressure of the dominant paradigm.

This is what is happening when you hear someone say, “I’m not THAT kind of vegan.” Though this may make it easier for the person expressing this sentiment to comfortably mingle with and feel more accepted by those who are still enabling the oppression, it works against our cause. We NEED people willing to speak out about injustice. When vegans say to others, “I am not THAT kind of vegan” it is a clear expression of judgement against people speaking out. It isolates activists. It makes other vegans contemplating speaking up feel shamed into silence. It supports and empowers the oppressive mindset. If our people – that is those choosing to abstain from intentional violence against other beings think we are wrong for daring to raise awareness of violence against animals, that plays right into and reinforces the oppressive paradigm. It also provides additional justification for non-vegans to disregard veganism altogether.

Can you think of a single example of progress made on any social justice issue, that was NOT the result of someone trying to push their values? That is why I continue to speak out and raise awareness however I can.

I will not apologize for speaking up when I see injustice, and the more people who join me in this, the better I believe our world will be.

After I wrote this essay, United Poultry Concerns invited me to discuss this subject further at their 2019 Conscious Eating Conference. Here is the video of the presentation that I gave there. I also wrote a blog post, Trading Patronage for Power in the Animal Right's Movement which discussed that event including the debate about clean meat, which was held that afternoon.